Share This

Hippie Squared: Me and the Buddhist Master

In keeping with Ernessa’s “Month of Minefields” I’m going to write about a subject I’ve touched on in poems, but never written about at length in prose, a subject rife with tricky territory and a few emotional minefields for me: religion; spirituality. Ah, let’s just say it plain: God. And/or the lack thereof.

In keeping with Ernessa’s “Month of Minefields” I’m going to write about a subject I’ve touched on in poems, but never written about at length in prose, a subject rife with tricky territory and a few emotional minefields for me: religion; spirituality. Ah, let’s just say it plain: God. And/or the lack thereof.

I propose to do this in two parts. This week: Me and the Buddhist Master. Next week: Seeing the Face of God in Burger King.

On a one-block idyllic dead-end lane in Kalamazoo, Michigan I was raised an atheist/agnostic among church-goers. Only one of the early developments that made me something of a mild but permanent outsider.

My dad was more the atheist and my mom more the agnostic. My dad’s antipathy to religion was intense and easily provoked. He’d been raised by a fundamentalist Christian grandmother who forbade him from playing with the Catholic girls down the street or playing baseball with black kids. Somehow he spotted the ignorance of it all and broke from her early. It didn’t take much to get him going about how most major wars had been fought in the name of religion.

Still, some Sundays I would go to church with my friend Fritz from across the street. He was always bored and would try to sneak out of the service. But I secretly liked it. His dad would give us quarters to put in the collection plate, but Fritz figured out a trick: stick your hand into the plate with the quarter and rattle the coins around, but palm the quarter. I did it out of peer pressure but I felt it was wrong.

I liked the sermons. I didn’t “believe,” but I liked to hear moral and philosophical questions taken up with such seriousness and intensity. Like that with which my mom and dad took up the subjects of racism, war, rejecting prejudice and knowing one’s own biases. I liked that there was a place where people came together once a week to consider weighty questions of right and wrong, and endings and beginnings, and the nature of what is or what isn’t. I didn’t have to agree with the foundations of their answers to relish the questions and the ponderings; the booming voice and the grand building; the singing and the collective reverence.

When I was probably about six two neighborhood girls just a few years older did an informal “Sunday school” with Fritz and I. We wrote out the lyrics to “Yes, Jesus Loves Me.” I showed my dad and asked him to read them to me. With a pained look on his face he refused. But he did not forbid me from taking the lessons or singing the song.

When I was about eleven, after the divorce, after my mom remarried, my step-dad Al took our new family to church every Sunday for awhile, as payment of a deal with his friend Charlie: if Charlie quit smoking, Al would go to church.

Sometime during that period I decided to hedge my bets: I tried to believe in God. I prayed each night, obsessing over asking God to bless every single person I knew, fearing the consequences of missing anyone. I also prayed to God to make me believe in him, because I really didn’t.

I finally decided it was all pretty silly. I realized that if God were omniscient, as the God I was trying to worship was said to be, he’d know damn well that I didn’t really believe in him and that I was just trying to cover the bases, trying to beat hell if it turned out I was wrong and it really did exist.

So I gave that all up, and embraced atheism. By then I was reading a lot of science fiction, thinking about being an astronomer or a physicist. Reading Asimov and Sagan. Learning that more atheists had read the bible than Christians and relating that statistic at every opportunity.

I’m not sure when I started getting the sense that I was somehow limiting myself. Now that I think about it, it was probably learning about Emerson and Thoreau and the Transcendentalists in junior year of high school. I felt a kinship to them, their notion of something undergirding and oversweeping that didn’t have a name or a theology attached.

In my twenties I discovered Taoism, and its foundational Tao Te Ching, still one of my favorite books, which I’ve read many times in many translations and dipped into for guidance or comfort hundreds of times. It was a religion that did not require a God.

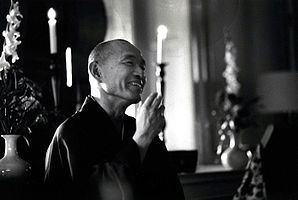

I also delved into Buddhism. My friend Angus and I took a ten-week class at the Zen Center of Los Angeles, a place I still return to every few years and which I love. At the end of ten weeks, you were granted a brief audience with the Roshi—the abbot of the Zen Center. Maezumi Roshi, in fact, who had received dharma transmission in two traditions: Soto and Rinzai Buddhism. That meant that he was enlightened.

Enlightenment was a concept that fascinated and attracted me. I wanted to believe in it. But I wasn’t sure I did. What could it be exactly? At the same time, I was struggling with squaring the Buddhism with my atheism, which I held onto. Was Buddhism a religion? Could you be an atheist and a Buddhist?

The Zen Center is a place of true calm and peace. It’s a compound of craftsman houses in what is now but was not then Koreatown. One of the things that won me to the place was the good humor of the monks there. They laughed and joked easily, and were always welcoming.

The meeting with the Roshi came after a session of meditation. I was ushered into a small room, where he sat on a zafu, a meditation cushion. I sat on my own cushion across from him. This is the sequence of events, but not of thought. Because as soon as I entered his presence I knew, to my complete and permanent satisfaction, that whatever enlightenment might be, it’s real. Whatever it is, this man had it. And no one else I’ve ever met had what he had. I’ve met some geniuses, I’ve met some old souls, I’ve met some wise men and women that I revere. They did not have what this man had. I can’t describe it. But I felt it and knew it. It’s simplistic to say it was calm, peace, presence, utter contentment with self, but it was these things and more.

His face held an effortless smile. He waited for me to sit, studying me gently and with an overwhelming compassion. He asked if I had any questions. I struggled with the one that burned in me, because on some level I knew it was irrelevant. Though I was nervous as hell I tried to keep my cool; tried to say it in a way that made me look smart, knowing, that indicated that I knew it might not be anything at all, but I just wanted to be sure.

“Well,” I said, “I just thought you ought to know that I’m an atheist.”

He looked at me with a great and gentle concern, but also a twinkle in the eye, and asked, “Is that a problem for you?”

The question took me so off-guard, it was so far from any response that I had expected, that I didn’t know what to say. I had worried that it would be a problem for him. He was telling me that it was not by reflecting the question back on me, and I had no real answer. Though I thought I did, and I spoke it. I sort of shrugged, and said, “No.” But I knew the answer was incomplete, an answer of the superficial intellect only.

He shrugged too, and smiled. And that was that. And it was many years before I realized that yes, in a way my atheism was a problem for me.

Let me add here, though, so you don’t move on in two weeks to part two of this essay with false expectations: expect no great conversion story. I have not taken any roads to Damascus. It ain’t that simple, and it ain’t that easy.

But I did see the face of God in Burger King. Or was that the back of his head?

Ya know, there are two forms of Taoism: the philosophic and, as you mentioned, the religious. The former has been around for thousands of years. The latter is less than 2000 years old.

From my perspective, the main benefit of the philosophical branch is that not only is there no god, but no religion to it either! It's merely a way of interpreting existence and each of us gets to discern what that means.

Exactly right, Rambling, that's part of what I loved about it then and still love about it. And I believe from your pseudonym that you've read "The Wandering Taoist."

Rambling, if you see Wandering, tell him I said hello.

Nope. Never read it.

Think about checking it out, it's a fun read. Good tale. More on the religious branch, with some martial arts action and some philosophical action all thrown in. About a Taoist monk in the early part of the last century in China. Well, anyway, I like your handle Rambling. Thanks for rambling on by.

Ya know, there are two forms of Taoism: the philosophic and, as you mentioned, the religious. The former has been around for thousands of years. The latter is less than 2000 years old.

From my perspective, the main benefit of the philosophical branch is that not only is there no god, but no religion to it either! It's merely a way of interpreting existence and each of us gets to discern what that means.

Exactly right, Rambling, that's part of what I loved about it then and still love about it. And I believe from your pseudonym that you've read "The Wandering Taoist."

Rambling, if you see Wandering, tell him I said hello.

Nope. Never read it.

Think about checking it out, it's a fun read. Good tale. More on the religious branch, with some martial arts action and some philosophical action all thrown in. About a Taoist monk in the early part of the last century in China. Well, anyway, I like your handle Rambling. Thanks for rambling on by.

Hey Rambling, I rambled on over to your site, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in Taoism. Here it is: http://ramblingtaoist.blogspot.com/. It’s thoughtful and thorough.

So not sure if “Wandering Taoist” is up your alley, Rambling, it’s definitely more on the religious Taoism side of things, with lots of ritual and superstition involved.

I’d be happy if you rambled on by by next week for the second part of my post; it won’t deal much specifically with Taoism, but it does deal with the inadequacy of religion in dealing with the true mysteries of the universe.

Hey Rambling, I rambled on over to your site, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in Taoism. Here it is: http://ramblingtaoist.blogspot.com/. It’s thoughtful and thorough.

So not sure if “Wandering Taoist” is up your alley, Rambling, it’s definitely more on the religious Taoism side of things, with lots of ritual and superstition involved.

I’d be happy if you rambled on by by next week for the second part of my post; it won’t deal much specifically with Taoism, but it does deal with the inadequacy of religion in dealing with the true mysteries of the universe.